Introducción

Nunca como ahora había estado tan presente el tema del patrimonio en la agenda de los medios de comunicación, en el espacio de los especialistas y en el escenario de la ciudadanía patrimonial. Sin duda que esta visibilidad y posicionamiento no es casual: ¡nunca se había destruido tanto patrimonio como ahora!

El proceso de destrucción selectivo y masivo del patrimonio se ha desarrollado sin el impedimento de los sujetos patrimoniales institucionales —nacionales e internacionales— encargados de velar su salvaguarda, tanto que estos no han reaccionado frente, por ejemplo, al derrocamiento de la Biblioteca de Alejandría, al bombardeo de Bagdad, a la invasión turística en Venecia, a la construcción de las grandes torres habitacionales en Santiago Centro o al vaciamiento de la sociedad en el Centro Histórico de Quito.[1]En 1990 la población del Centro Histórico fue 81.384 habitantes, 20 años después se redujo a 40.913 (Del Pino, 2013). Es más, en muchos casos, sus propias acciones han sido las que han deteriorado el acervo acumulado.

Esta debilidad institucional pone en cuestión su condición estructural y también los paradigmas tradicionales con los que han abordado la temática.[2]Los paradigmas hegemónicos han sido funcionales a estos procesos, por ejemplo, gracias a las políticas de turismo, de gentrificación y de conservación, entre otras. En otras palabras la destrucción patrimonial, la debilidad institucional y la obsolescencia conceptual —en el marco de la globalización— configuran una coyuntura patrimonial signada por la producción de olvido, que bien podría caracterizarse como una crisis global del patrimonio; muy similar a la que se produjo luego de la Segunda Guerra Mundial,[3]Situación muy parecida se vivió con la Segunda Guerra Mundial en Europa, que dio lugar justamente a un impulso muy fuerte de las tesis de la restauración y la reconstrucción monumental. con la diferencia de que ella estuvo localizada en Europa y la actual se despliega de manera generalizada en el territorio y de forma ubicua;[4]Tres grandes coyunturas patrimoniales ha vivido la humanidad: la primera con la primera modernidad, la segunda con la guerra mundial y ahora con la globalización. lo cual es posible porque se ha producido la globalización del patrimonio, gracias a la revolución científico-tecnológica en el campo de las comunicaciones, a las declaratorias de patrimonio de la humanidad,[5]Al momento son 187 ciudades consideradas patrimonio de la humanidad, las que deciden conformar la Organización de Ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad (OCPM), para intercambiar experiencias, difundir … Continue reading al peso de la cooperación internacional y al turismo homogeneizador que rompe fronteras.

Es que ahora el patrimonio se revela como una construcción social y, por lo tanto, como un fenómeno histórico que muta constantemente; por eso existen coyunturas particulares de transformación de sus modos de (re)producción. Este es el caso de toda crisis, porque se convierte en un par de aguas, que divide e integra momentos distintos.

La crisis patrimonial es una oportunidad que se empiezan a sentir como un punto de partida de una nueva realidad: nace de la queja social en crecimiento, de la reivindicación ciudadana que presiona y, sobre todo, del aparecimiento de ciertos atisbos de proyectos colectivos alternativos. En esa perspectiva y en esta coyuntura se vive la confrontación de dos modelos de gestión que buscan la salida a la crisis: el uno bajo la égida del mercado (acumulación) y el otro desde el peso de lo público (democratización); pero no es solo en el ejercicio de gobierno, sino también en la concepción del patrimonio, lo cual le pone al concepto, por primera vez, en una doble condición creativa: superar el fetichismo patrimonial y aceptar la condición polisémica que tiene.

Con este trabajo se quiere aportar al conocimiento de esta coyuntura patrimonial mediante un giro metodológico: a la visión monopólica del patrimonio como bien depositario de la memoria (monumento),[6]Por monumento se entiende según el DRAE: “Obra pública y patente, como una estatua, una inscripción o un sepulcro, puesta en memoria de una acción heroica u otra cosa singular. Construcción … Continue reading se busca oponer el sentido de la producción del olvido; de tal manera de reconstruir el equilibrio en la ecuación patrimonial entre: la acumulación del pasado (acervo) y la destrucción del presente (despilfarro), pero desde sus procesos sociales constitutivos.

Si tradicionalmente se han resaltado los atributos del bien patrimonial —vinculados generalmente a lo monumental— hoy lo que está en discusión son las relaciones sociales que explican la pérdida del acervo continuamente acumulado a lo largo de la historia.[7]Acervo: conjunto de bienes morales o culturales acumulados por tradición o coherencia. En otras palabras, concebir al patrimonio menos a partir de los atributos y más desde relaciones sociales que lo constituyen. Pero también se trata de llamar la atención desde el ángulo inverso a la cantidad de memoria acumulada; esto es, desde las lógicas y formas de producción del olvido, de tal manera de entender los procesos de generación patrimonial por sus orígenes (económicos, culturales, políticos), y menos a partir del objeto de la destrucción (monumento); para construir nuevas maneras de producir sustentabilidad en la acumulación histórica del patrimonio (valor de historia).

Este giro metodológico permitirá curar con el ejemplo, pero al revés: mirar desde lo que se pierde, a través de un balance entre lo que se recupera y se destruye, en aras de supuestos “valores superiores” provenientes de la política, de la guerra o de la economía, que terminan por subsumir a las propias instituciones destinadas a mitigar el olvido.

El concepto urbicidio es central en la comprensión de este proceso, porque ayuda a entender lo que se pierde y, a partir de ello, lo que se debe mantener y también construir.

Lo patrimonial: polisemia y fetichismo

Según el diccionario de la Academia de la Lengua, la palabra patrimonio viene del latín y se compone, por un lado, de patri que significa padre, y por otro, onium que quiere decir recibido; es decir: es recibido por línea paterna. De allí que sea una definición altamente dinámica que entraña un proceso histórico que tiene actores explícitos: los que reciben (es recibido por) y el que transmite (por línea paterna); es decir, actores que interactúan a la manera de sujetos patrimoniales en relación a la disputa de la heredad (Carrión, 2010).

Esta noción de patrimonio no define bienes o cosas (cosifica) —sean materiales, inmateriales o espirituales— sino una relación que delimita un ámbito particular del conflicto social: el legado o la herencia, y lo hace según la correlación de fuerzas de los sujetos patrimoniales en un momento y en lugar particulares; que es, finalmente, la que define la condición de poder de cada uno de ellos, porque sin apropiación —como base del poder— no hay patrimonio.

Es en el contexto de los mecanismos de transmisión del patrimonio —propios del procesamiento del conflicto— que se logra la sustentabilidad histórica del proceso, situación muy similar a lo que ocurre al interior del núcleo familiar entre el padre y sus hijos. O sea que el patrimonio genera un poder que nace de la propiedad y del peso que los sujetos patrimoniales tienen en su interacción: alguien debe apropiarse para que exista el patrimonio y, sin duda, la propiedad es una relación social históricamente constituida.

De esta manera, lo patrimonial es el resultado del proceso histórico de acumulación continua de tiempo y, a su vez, es un mecanismo productor de historia; todo ello gracias a la transformación constante de la masa patrimonial (acervo) mediante la transmisión del patrimonio entre los sujetos, bajo una doble situación: democratización del patrimonio (propiedad y poder) e incremento del valor de historia (añade tiempo al pasado); que en nada tienen que ver con las políticas de conservación. Esta historicidad de la relación social —que define la heredad productiva— niega el fetichismo patrimonial así como las prácticas de contención de la historia en su único momento: el origen.

En última instancia el patrimonio entraña, por un lado, una propiedad que le otorga al sujeto patrimonial un poder. Y, por otro, una transferencia o heredad que —por más familiar y privada que sea— debe ser ventilada por el sector público, en tanto son las cortes de justicia (marco institucional público) y la normativa del código civil (pacto social) los que determinan el protocolo que debe seguirse. Lo patrimonial en el ámbito de la sociedad no es muy distinto: el conflicto debe ser procesado con normas jurídicas, instituciones y, también, con políticas públicas porque, caso contrario, será el mercado que lo haga desde su propia lógica; mucho más si —como ahora ocurre— existen procesos de desregulación que tienen como fundamento atraer capitales (condiciones generales) que transforma el patrimonio en capital físico.

El patrimonio solo puede ser concebido históricamente porque existe una lógica de poder sustentada en las relaciones de los sujetos patrimoniales que lo (re)producen, transfieren y consumen. Si esto es así, se pueden encontrar tres grandes coyunturas patrimoniales a lo largo de la historia: la primera, vinculada a la modernidad, cuando el Estado se apropia del patrimonio (patrimonio institucional), para concebirlo como un “aparato ideológico” que construye y legitima la historia oficial, gracias al disfrute que genera su espectacularización y a la masificación de su consumo contemplativo,[8]Posteriormente adquirirá un peso singular el valor de cambio, justamente cuando el modelo capitalista se consolida y cuando el turismo y el sector inmobiliario le dan una nueva connotación al … Continue reading venido de la hiperurbanización de la población.

En este momento —característico como coyuntura patrimonial— se produce el hecho fundacional del nacimiento del patrimonio histórico —porque el patrimonio no ha existido siempre— a partir de dos vías constitutivas: por un lado, de los monumentos construidos con una función social relevante, como puede ser la misa (valor de uso), pero que requieren su perdurabilidad en el tiempo, como testimonio de una época sea por la importancia de la función que desempeñaba o por la riqueza de su producción material. En este caso lo que se tiene es el incremento a su cualidad funcional (valor de uso) la necesidad del sentido de memoria (valor de historia). Y por otro, por la necesidad que existe por hacer público un hecho histórico del ayer,[9]Tanto el uno como el otro producen “historia oficial”. a través de la construcción explícita de un nuevo bien patrimonial (monumento) que desde el principio nazca con valor de historia, como si fuera su valor de uso. En este momento se diferencia patrimonio como valor de uso, del patrimonio histórico como valor de historia.

La siguiente coyuntura está relacionada con el período de ambas guerras mundiales, cuando se producen destrucciones significativas del patrimonio histórico europeo, localizado en las ciudades más emblemáticas. A partir de este momento Europa se convierte en el espacio principal de irradiación del pensamiento —sobre todo— de las políticas del patrimonio que se universalizaron acríticamente.[10]La Segunda Guerra Mundial destruyó de un día para otro el patrimonio de las ciudades, mientras en América Latina la erosión vino de las condiciones socioeconómicas y de las características de … Continue reading Para formalizar estas propuestas se utilizaran las denominadas Cartas —que adoptaran el nombre de la ciudad donde se las redacta—[11]La Carta de Atenas (1931) fue redactada solo por especialistas europeos, en la de Venecia (1964) par-ticiparon tres “extraños” provenientes de Perú, México y Túnez y luego en 1972 se realizó … Continue reading y las Convenciones, las dos bajo el principio de la conservación monumental en sus distintos grados, que fueron incapaces de comprender la riqueza de los fenómenos particulares y, mucho menos, de detener los procesos destructivos.

La condición histórica del patrimonio supera aquel paradigma[12]Según Tomas Kuhn “(…), el paradigma hace referencia al “conjunto de prácticas que definen una disci-plina científica durante un período específico”. dominante de lo patrimonial sustentado en la devoción por ciertos bienes —como objetos esenciales, sean tangibles o intangibles, materiales o inmateriales— que devino en el fetichismo patrimonial,[13]En mucho se acerca a la propuesta de Marx (2000) respecto del sentido y contenido del “fetichismo de la mercancía”. en tanto deja por fuera las relaciones sociales que las (re)producen o las esconden tras los atributos del bien. Esta visión histórica[14]Aquí se inscribe esa definición del “patrimonio monumental colonial” como determinación de exis-tencia de un centro fundacional de valor en América Latina que, incluso, termina por definirlo … Continue reading se concreta en la producción social del patrimonio, ocurrida en momentos, en lugares y en sociedades particulares.

Los centros históricos, por ejemplo, fueron concebidos como un bien físico que tenía ciertos atributos (conjunto monumental) y no relaciones. Por eso cuando a los centros históricos se los analiza históricamente, como producción social, la cualidad central —que es una definición relativa— se hace líquida; y la condición histórica se reduce a encontrar el momento de su génesis para aplicar las políticas de conservación. De esta manera se lo vacía de historia y se llena de fetichismo, por eso, la conservación produce la negación de la condición histórica del centro histórico; tanto que al poner en valor el bien patrimonial producido durante la conquista española, realza la dominación colonial a través de los atributos que se le asignan al monumento —o al conjunto monumental— y congela la historia en el momento de su origen, lo cual niega el proceso continuo de acumulación del tiempo en el pasado que permite múltiples y simultáneas lecturas provenientes de tiempos distintos bajo la forma de un palimpsesto (valor de historia).

De esta manera la condición histórica se licúa cuando lo monumental se convierte en el elemento determinador de la existencia del patrimonio y no al revés: lo patrimonial es una herencia o transmisión creativa que produce un incremento del valor de historia del bien. Por eso no aceptan que, por ejemplo, la demarcación de un centro histórico nazca de la política urbana y de la correlación de fuerzas de los sujetos patrimoniales y sí creen que la delimitación viene de un demiurgo creador que cae del cielo, encarnado por una deidad o por un técnico.

Como reacción a este fetichismo patrimonial han aparecido dos visiones. La una, entendida como capital físico que debe reproducirse y acumularse, de tal manera de obtener ganancias económicas significativas (valor de cambio); en esa perspectiva el turismo es gravitante, aunque también lo es lo comercial y el sector inmobiliario (Rojas, 2004). Y la otra, que empieza a dar sus primeros pasos desde el concepto de patrimonio como capital social, en tanto permitiría fortalecer las instituciones y mejorar la cohesión social.

El patrimonio histórico es además, en la actualidad, una definición polisémica[15]Como también lo son los conceptos de democracia, desarrollo y descentralización, entre otros. porque tiene múltiples y plurales formas de concebirlo, tanto que rompe con definición hegemónica inscrita en la lógica del pensamiento único, que no acepta disidencias. A continuación podemos ver varias entradas que nos muestran esta realidad:

- El itinerario histórico —propio del transcurrir de los tiempos— que da lugar a una secuencia que, según Choay (2007), transita de la connotación familiar (patrimonio familiar), a la economía (patrimonio económico), al campo jurídico[16]Este reconocimiento de lo jurídico tiene dos implicaciones muy importantes: primero, se ubica en el campo del derecho y, segundo, lo convierte en un proceso público que está normado —a través … Continue reading y luego sigue por al ámbito político (patrimonialismo),[17]Se refiere a los sujetos patrimoniales (patriarcales) que consideran como propios los bienes públicos; es decir, se apropian de lo público todas ellas con un peso singular del sentido propiedad. Patrimonio es, entonces, lo que se posee bajo diferentes formas que el derecho termina por formalizarlas.

- La fragmentación en tipos patrimoniales se expresa bajo tres situaciones: la primera vinculada a su carácter dicotómico, material o inmaterial, así como tangible o intangible; la segunda relacionada con el ámbito sectorial del patrimonio: industrial, cultural, militar, arquitectónico, musical; y la tercera referida a lo que Bourdieu (1999) denominó el “efecto lugar”, que plantea un universo patrimonial según el espacio donde se construya. Como históricamente el concepto nace en Europa —en la modernidad— es este el punto de partida desde donde se irradia al mundo; cosa que ahora no es posible por la emergencia de nuevas realidades a nivel planetario;[18]“Mi labor en el continente americano durante más de veinte años, en contraste con el trabajo en mi país y resto de Europa, me ha hecho observar que para resolver el problema de la conservación … Continue reading este es el típico caso del sentido de la glocalización —definida por Robertson (1992)— del patrimonio, que lo pluraliza. La riqueza del universo patrimonial radica en su acumulación (noción de antigüedad) y en su diversidad.

- Las posiciones teórico-metodológicas definen las características del objeto de pensamiento: la visión tradicional pone énfasis en el denominado bien patrimonial, sea material o inmaterial, que es probablemente la más extendida. Esta visión está en franco cuestionamiento a partir de tres posiciones que se empiezan a trabajar: la una, que surge de la definición del capital físico que debe reproducirse con altas tasas de ganancia (Rojas, 2004) y la otra desde lo que significa el capital social que fortalece las instituciones y la cohesión social. Adicionalmente se encuentra la que se concibe como un escenario de conflicto entre sujetos patrimoniales alrededor de la transmisión sustentable de la herencia.

Así como lo polisémico es un avance, también lo es la superación del fetichismo patrimonial, uno y otro inscritos bajo una condición histórica. Pero también es el hecho de que el proceso de urbanización de la sociedad ha determinado que la ciudad sea el espacio con más alta densidad de patrimonio, tanto que todo lo que contiene una urbe es patrimonial, porque la totalidad de la ciudad y sus partes, tienen un valor de uso. Sin embargo, solo algunas partes adquieren la condición de patrimonio histórico, gracias a la acumulación continua del valor de historia. Por eso el urbicidio puede actuar sobre el patrimonio, el patrimonio histórico o sobre los dos; dependiendo las estrategias diseñadas.

Urbicidio: producción social de olvido

El concepto urbicidio nace en la década de los años sesenta de la mano de Michael Moorcock en el ámbito de la literatura (1963). Deberán pasar unos años más para que se lo empiece a utilizar en el campo de los estudios de la ciudad, a través de dos entradas metodológicas distintas: la primera, relacionada con los efectos devastadores que producen las guerras en las ciudades y la segunda, vinculada explícitamente a los impactos que genera la refuncionalización de las ciudades, sobre todo en aquellos lugares donde habitan los sectores populares, como ocurrió en Nueva York (Bronx) o en Chicago. Después de estos dos intentos —el uno en que la ciudad actúa como escenario y el otro como parte constitutiva de la ciudad— el concepto prácticamente desapareció por la supuesta falta de comprensión de la realidad urbana.

Sin embargo, esta noción debe trabajarse porque tiene una riqueza muy grande para explicar algunos de los fenómenos propios del urbanismo neoliberal que viven las ciudades de América Latina, y mucho más si se lo vincula al concepto de patrimonio, que en este contexto histórico se transforma en capital físico. De allí que alrededor de la relación entre urbicidio y patrimonio sea factible encontrar la riqueza de su formulación.

El urbicidio es un neologismo que encarna una palabra compuesta por: urbs que es sinónimo de ciudad y cidio de muerte: esto es, la muerte de la ciudad.[19]Término que viene del latín: urbs, ciudad; caedere, cortar o asesinar y occido, masacre. Pero así como el homicidio expresa el fallecimiento de una persona, el femicidio de una mujer por razones de género o el suicidio de un ser humano de forma autoinfligida, el urbicidio no es la muerte de todas las urbes, ni tampoco el fin de la ciudades como realidad compleja; sino, más bien, del asesinato de una ciudad en particular o de ciertos componentes esenciales de ella, por procesos claramente definidos.

Se puede afirmar que se trata de un concepto en construcción que tiene que ver con al asesinato litúrgico de las urbes cuando se producen agresiones y acciones con premeditación, orden y forma explícita. Es decir, se trata del asesinato o de la violencia en contra de la ciudad por razones urbanas. En principio son acciones militares, económicas, culturales o políticas que: i) acaban con la identidad, los símbolos y la memoria colectiva de la sociedad local concentrada en las ciudades; así como cambian el sentido de la ciudadanía por el de cliente o consumidor (civitas); ii) privatizan, concentran o subordinan las políticas y las instituciones públicas a los intereses del mercado o del poder central, perdiendo las posibilidades del autogobierno y de la representación (polis); y iii) arrasan con los sistemas de los lugares significativos de la vida en común, como son las plazas, los monumentos, las infraestructuras (puentes, carreteras) y las bibliotecas (urbs).

Para ilustrar esta afirmación y, a manera de ejemplo, se pueden señalar los siguientes casos emblemáticos de producción social del urbicidio:

1. Probablemente lo más evidente tenga que ver con las guerras y las luchas fratricidas desarrolladas a lo largo del mundo entero y desde tiempos inmemorables, aunque hoy con el añadido de que su escenario principal, por la urbanización planetaria, son las ciudades. Sin retrotraerse mucho en el tiempo están los siguientes casos de este tipo de devastación de ciudades:

- La emblemática ciudad de Guernica —destruida en 1937— es importante porque fue un ensayo de los bombardeos masivos que vendrían después en la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Pero adicionalmente porque se trató de una incursión aérea devastadora, ejecutada por fuerzas italianas y alemanas en el marco de la Guerra Civil Española. Los puntos estratégicos que debían ser aniquilados eran: el puente, la estación de ferrocarril y la carretera del este de la ciudad, supuestamente para contener a las fuerzas vascas. Sin embargo el objetivo real fue el de la destrucción de la ciudad de Guernica, por su condición de capital cultural e histórica del país Vasco y por ser un santuario de afirmación de su libertad y de su democracia; contrarios al poder monárquico, centralizado y fascista encarnado por Franco. Allí la explicación de más del 7% de la población muerta, del 74% de los edificios destruidos y de la reducción de la moral de los vascos.

- Entre los impactos que se produjeron durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, entre muchas ciudades que pueden mencionarse, están Varsovia, Berlín, Tokio y, sobre todo, Hiroshima y Nagasaki. Las primeras ciudades citadas sufrieron hechos de violencia militar en tanto escenario de la guerra o como ciudades de la guerra a las que había que destrozarlas; mientras las dos últimas fueron arrasadas como parte de una ofensiva que buscaba mostrar la supremacía de un país sobre el resto del mundo, justo cuando la guerra llegaba a su fin.

- A partir de la década de los años noventa del siglo pasado se desarrollan nuevas guerras en dos escenarios: la de los Balcanes, que como señala el ex alcalde de Belgrado, Bogdan Bogdanovic, explícitamente fueron antiurbanas, destinadas a socavar los valores culturales concentrados en las ciudades. Allí están las urbes de Sarajevo, Belgrado, Móstar, Grozni. Pero también están las ciudades que fueron el epicentro de la escisión de la Unión Soviética y de la conformación de la Federación Rusa, en las que sobre salen las naciones de Chechenia y Georgia, entre otras.

- Luego vinieron las guerras “preventivas” impulsadas por George Bush, Presidente de los EEUU o las “guerras necesarias” generadas por el Premio Nobel de la Paz, Barack Obama, que utilizaron el pretexto del aleve ataque de los Talibanes —el 11 de septiembre de 2002— a los Estados Unidos en los lugares con la mayor carga simbólica de ese país: las Torres Gemelas de Nueva York como expresión del poderío económico, el Pentágono en Washington lugar del Departamento de Defensa y la Casa Blanca, que no llegó a concretarse, como expresión del poder político de los EE.UU. La reacción inmediata fue la invasión a Irak y a Afganistán, donde las ciudades emblemáticas de Bagdad, capital de Irak, como Kabul, capital de Afganistán, entre otras, sufrieron la destrucción del patrimonio por medio de sanciones, saqueos y ataques militares.

- No se puede dejar de mencionar las conflagraciones acontecidas en la zona árabe; allí los casos más significativos son los de Libia (Trípoli, Bengasi) y Siria (Damasco, Alepo), además de los países inscritos en la llamada primavera árabe como: Túnez, con la capital que lleva el mismo nombre, y Egipto con El Cairo y Alejandría.

- Se deben resaltar los conflictos que tienen larga duración, como son los ejemplos de los casos: Árabe-Israelí, en que Jerusalem, Haifa, Gaza y tantas más sufren los efectos culturales de la guerra permanente. Tampoco se debe dejar pasar por alto el conflicto interno colombiano, al que se han sumado los ingredientes provenientes de las economías ilegales (drogas, armas, precursores químicos, tratas) para destruir ciudades de manera terrorista. Y mucho menos olvidar los efectos de la guerra civil libanesa, de los ataques israelíes y de la confrontación interna entre cristianos y musulmanes que dejaron en soletas al patrimonio milenario de la ciudad Beirut y a sus habitantes.

En general estos casos presentan el enfoque militar de estrategias y tácticas para someter a las ciudades adversarias —física y moralmente— mediante: el asesinato de personas (selectivo, masivo), el aislamiento (aeropuertos, puentes), la restricción de los servicios (energía eléctrica, agua potable), el bloqueo del abastecimiento (comida, repuestos) y, además, la acción exclusivamente simbólica sobre los monumentos, los lugares de encuentro, las iglesias, las mezquitas y las bibliotecas, todos ellos signos urbanos de la vida en común.

2. Un segundo elemento productor de urbicidio —que no se puede dejar de mencionar— es la violencia urbana, sobre todo porque en estos últimos 20 años, al menos en América Latina, ha existido un aumento considerable de los homicidios en las ciudades.[20]Si se mide por la tasa de homicidios se tiene que en 1980 era de 12 por cien mil habitantes, cosa que para 2006 subió a 25, 3 (Klisberg, 2008). Si antiguamente se creía que la ciudad era una causa de la violencia —por la vía de la etiología— hoy se puede afirmar que mucho más impactos negativos produce la violencia en la ciudad, tanto es así que la violencia objetiva (los hechos producidos) y la violencia subjetiva (el temor) se han convertido en principios urbanísticos que tienden a negar la ciudad bajo la modalidad del urbicidio.

- La violencia urbana se despliega en el tiempo bajo una lógica temporal claramente marcada: el calendario cultural hace que cada semana sea diferente, los fines de semana sean distintos a los días laborales; las horas de la noche difieran a las del día. Claramente hay una cronología delictiva que le afecta a la dinámica urbana y a la ciudad en sí misma, tanto que en términos generales se observa una reducción significativa del uso de la ciudad: ya no existe una ciudad de 365 días, de 54 semanas o de 24 horas.

- La violencia en la ciudad tiende a desarrollarse en el espacio, pero bajo una lógica urbana explícita que afirma la existencia de una geografía delictiva que —poco a poco— se toma la ciudad, sea con la percepción de inseguridad o con los diversos hechos delictivos. La percepción de inseguridad es difusa y ubicua, aunque afín a los estigmas territoriales; mientras la realidad de los hechos delictivos se origina en la fragmentación urbana existente: se roban bancos donde hay bancos, la criminalidad del centro es distinta a la de la periferia, la violencia en el espacio público difiere de la del espacio privado.

- Adicionalmente la violencia en las ciudades, como parte de la interacción social, produce efectos devastadores en la convivencia social y en la vida cotidiana, tanto que se reducen las condiciones de solidaridad y se amplían las múltiples modalidades de justicia por la propia mano, que van desde adquirir armas, aprender defensa personal, linchar personas y convertirse cliente de la boyante industria de la seguridad privada. Pero también, porque todo desconocido se convierte en un potencial agresor y porque el espacio público es considerado un espacio fuera de control (Carrión, 2010).

Sin duda que la violencia urbana reduce sus bases esenciales: el tiempo, el espacio y la ciudadanía y también, por la falta de respuesta positiva, las instituciones y las políticas se desacreditan. Esto es, el urbicidio tiene en la violencia una fuente de existencia importante, porque —simultáneamente— construye el olvido y destruye la memoria.

3. Uno de los impactos más significativos provienen de la economía y el emplazamiento de la lógica de la ciudad neoliberal.

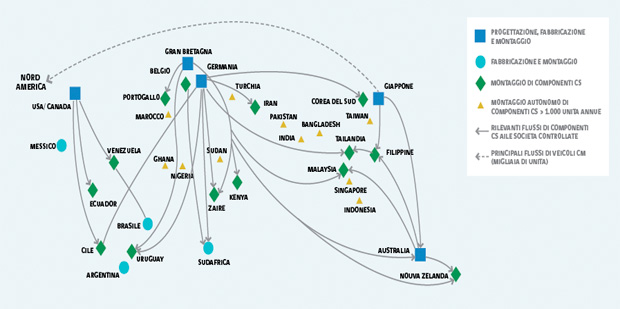

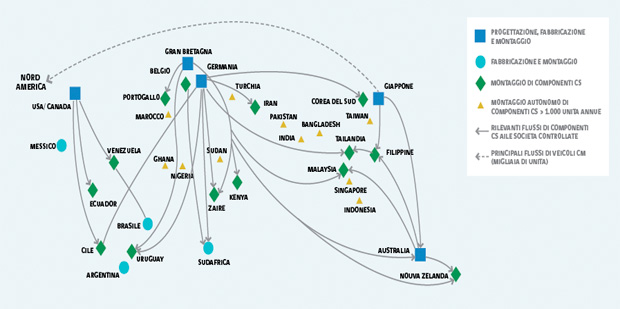

- La modificación y el desplazamiento de las condiciones generales y estructurales de la acumulación producen, por ejemplo, la crisis irreversible de la ciudad de Detroit.[21]La población se ha reducido a la mitad en los últimos 50 años, el desempleo es el triple del año 2000, el 47% de las propiedades no pagan los impuestos municipales, existe una deuda municipal … Continue reading El cambio global del modelo de producción de una ciudad inicialmente nacida y desarrollada alrededor de la industria automotriz —cuando este poderoso sector de la economía se amparaba en una forma de producción concentrada en un espacio específico— cae en una profunda depresión debido a la descomposición y a relocalización del conjunto de los procesos de producción a nivel planetario, con lo cual la urbe queda por fuera de los nuevos circuitos económicos, tal cual se describe en el siguiente gráfico realizado por Celata F. (2007):

Estructura productiva de General Motors

- Por otro lado y desde una perspectiva microeconómica e intraurbana, también se producen procesos de urbicidio, gracias a los siguientes elementos: i) al crecimiento del peso que tiene el capital de promoción inmobiliario dentro de la economía urbana; ii) a la presencia de los grandes proyectos urbanos (GPU) venidos de la crisis de la planificación urbana y de la demanda del sector inmobiliario; y iii) a la transformación de la ciudad segregada por la ciudad fragmentada —propia de la “ciudad insular” (Duhau) —, que genera una constelación de espacios discontinuos constituidos con “lugares de excepción” o “zonas francas” donde el urbanismo de productos —que responde a los negocios privados— se instala para colonizar el espacio y expulsar a la población de bajos ingresos bajo la lógica de la gentrificación.

Estos lugares de excepción se nutren del urbanismo a la carta que genera una normativa pública afín a las reivindicaciones del sector inmobiliario que se formalizan en los eufemismos de los planes parciales, de las fórmulas de desregulación del mercado del suelo e inmobiliario o de los incentivos tributarios. Finalmente se expresan en cambios de los usos del suelo, en la modificación de las densidades, de las alturas de las edificaciones, así como en la exención impositiva y la generación de créditos subsidiados, formando un verdadero enclave que rompe con la lógica del espacio público, de la prestación homogénea de los servicios y de la expulsión de la población de bajos ingresos; fortaleciendo la segregación urbana, erosionando el capital social y debilitando el gobierno de la ciudad.

4. No se puede desconocer la lógica de la innovación que reina mundialmente y que proviene de la revolución científico-tecnológica en el campo de las comunicaciones es, obviamente, contraria a la conservación y a la memoria, porque a la par viene con la tesis del de que el éxito depende de la velocidad del cambio; por eso todo termina por volverse obsoleto en plazos muy cortos y hace que lo viejo ceda a lo nuevo.

5. Finalmente un elemento que debe ser considerado como urbicidio tiene que ver con el cambio climático y las secuelas urbanas que está produciendo. La vulnerabilidad del planeta ha crecido y lo ha hecho de manera desigual en términos sociales y territoriales. Los casos de los terremotos y tsunamis en Chile y Haití; de los ciclones en Centro América y Filipinas; las inundaciones en China y Nueva Orleans y las sequías en Australia están produciendo efectos devastadores en las ciudades y en las poblaciones que las habitan.

En definitiva, el urbicidio hace referencia, por un lado, a las prácticas destinadas a la producción del olvido; cuestión que en la actualidad se enmarca en el llamado choque de civilizaciones. Se trata de procesos y no de hechos puntuales, que se inscriben en contextos muchos más amplios. Se busca destruir la memoria histórica de la ciudadanía que opera como mecanismo de cohesión social y de identidad colectiva (civitas) para someter a esos pueblos a las lógicas de sociedades supuestamente más desarrolladas.

Pero también, por otro lado, el urbicidio vinculado principalmente a la economía urbana conduce a la erosión de la institucionalidad y del autogobierno (polis) mediante las privatizaciones o la corrupción, así como el deterioro de la base material de una ciudad (urbs), en aras de un supuesto desarrollo urbano inscrito en la lógica de la ciudad neoliberal.

(IN)Conclusiones

No se trata de presentar conclusiones en este trabajo, porque es un tema abierto y en proceso de construcción. Sin embargo, sí se debe señalar que el patrimonio como el urbicidio son construcciones sociales y por lo tanto históricas. Esta primera constatación conduce a la afirmación de que el patrimonio se revela en esta coyuntura como una definición polisémica y como un concepto que supera al fetichismo patrimonial, que lo caracterizó desde su inicio y que lo condujo al vaciamiento de la sociedad.

La lógica del monumento sin historia o del patrimonio sin sociedad es una realidad que no puede seguir siendo aceptada y que debe ser superada. No es posible que a la memoria —que es un espacio de confrontación— la vaciemos de historia (¿el fin de la historia que algunos pregonaban?) cuando lo que hay que hacer es todo lo contrario: sumarle todos los tiempos, incluso el sentido de futuro a la manera de un objeto del deseo y distribuirla equilibradamente en la sociedad. Para ello es imprescindible construir un proyecto colectivo del patrimonio, con los sujetos patrimoniales más significativos y desarrollar visiones integrales y multidisciplinares, que vayan más allá de los cónclaves y de las tecnocracias tradicionales.

La ciudad es el lugar con mayor cantidad de población concentra en el mundo, es el espacio con la más alta densidad de patrimonio del planeta y también es el territorio donde se expresa su mayor diversidad medida por el valor de uso (patrimonio), valor de historia (patrimonio histórico) y valor de cambio (patrimonio económico); por eso la producción social del urbicidio conduce a la pérdida de la memoria y a la producción de olvido del conjunto de la humanidad. Además como el patrimonio es la esencia de la cohesión social y de las identidades múltiples que adornan a la ciudadanía universal, no podemos seguir siendo indolentes ante estos delitos atroces de lesa humanidad que están ocurriendo alrededor del mundo.

El patrimonio es un asunto de ciudad de notable importancia y las centralidades urbanas (que todas son históricas) es el espacio de la urbe con mayor carga de patrimonio histórico; motivo por el cual es imprescindible desarrollar políticas urbanas. Pero como el urbicidio se nos presenta desde varias matrices (guerra, economía) es ineludible construir ciudades para la paz, economías urbanas sólidas y bien distribuidas, políticas culturales que respeten la diversidad, políticas que incorporen la tecnología de punta y políticas ambientales que contengan el cambio climático global, entre otras.

El urbicidio aparece para dar cuenta de la necesidad de reivindicar el derecho a la ciudad y de producir un urbanismo ciudadano, porque la democratización del patrimonio es una forma de democratizar la ciudad. Más aún si se tiene en cuenta que se está produciendo urbanización sin ciudad, que hay procesos urbanos que niegan la ciudad y que el espacio público termina siendo guarida antes que interacción.

Por eso no se puede dejar de plantear la disyuntiva respecto del patrimonio: ¿es de la humanidad o del mercado? Y tampoco dejar de afirmar que el antídoto al urbicidio es el derecho a la ciudad, porque la ciudad y sus partes son patrimoniales.

Fernando Carrión M.[22]Presidente de la Organización Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Centros Históricos (OLACCHI) y académico de la Facultad Latinoamérica de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) en Quito, Ecuador.

Introduction

Never before has the subject of heritage been more present in the agenda of the media, on the minds of specialists, or on the stage of citizen heritage. Without a doubt, this positioning and visibility is not by chance: never before has so much heritage been destroyed as today.

The process of selective and massive destruction of heritage has grown without the opposition of those institutions —national and international— that are in charge of safeguarding said heritage. These institutions have not reacted, for example, even with the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, the bombing of Baghdad, the tourist invasion of Venice, the construction of enormous residential buildings in downtown Santiago, or the emptying of people from the Historical Center of Quito.[23]In 1990 the population of the historical center was 81.384 inhabitants, 20 years later it is down to 40.913 (Del Pino, 2013). Furthermore, in many cases their very own actions have been those that have deteriorated the accumulated heritage.

This institutional weakness puts in doubt the structural condition as well as traditional paradigms that have addressed this topic.[24]The hegemonic paradigms have been functional in these processes, for example, thanks to politics of tourism, of gentrification and conservation, among others. In other words, the destruction of heritage together with institutional weakness and conceptual obsolescence —within the framework of globalization— has created awareness of the production of oversight, which could very well be characterized as a global heritage crisis; very similar to what happened following the Second World War,[25]Situation very similar to that lived during the Second World War in Europe that created a strong impulse for studies on restauration and reconstruction of monuments. with the difference being that this was in Europe, while the current crisis is ubiquitously[26]Three great patrimonial moments have been experienced during humanity: the first with modernity, the second with the world war, and now with globalization. spread out over the territory. This is only possible due to the globalization of heritage, and thanks to the scientific-technological revolution in the field of communications, in the declarations of human heritage,[27]Currently there are 187 cities that are considered world heritage sites, which decided to form the Organization of World Heritage Sites, as to exchange experiences, spread knowledge, and generate … Continue reading and the weight of international cooperation and homogenization of tourism that breaks down frontiers.

Patrimony now reveals itself as a social construction, and therefore, as an historical phenomena that is in a state of constant change; this is why there are certain moments that move away from tradition forms of (re)production. This is the case of this crisis, since it is more similar to water, in that it divides and converges at different points in time.

The heritage crisis is an opportunity that is beginning to feel like a starting point for a new reality: it is born from rising social discomfort, from citizen revindication that pressures, and above all, brings to light certain traces of alternative collective projects. Within this perspective and in these circumstances we witness the argument of two management models, which are searching for a way out of this crisis: one underneath the aegis of the market (accumulation) and the other from the weight of the public (democratization). However, this is not only in the hands of the government, but also in the conception of heritage, which places the concept for the first time as a double creative condition: by surpassing heritage fetishism and accepting the polysemic condition it has.

The aim of this paper is to help towards the understanding of the current heritage situation through a methodological change: from a monopolistic vision of patrimony as a depository of memory (monument),[28]A monument is understood as, according to DRAE: “Public Work and patent, like a sculpture, an inscription or a sept, placed in memory by an heroic action or something similar. Construction that … Continue reading there is an attempt to stop the production of oversight in such a way that it rebuilds the equilibrium present in the heritage equation between the accumulation of the past (heritage) and the destruction of the present (squandering), but from its constitutive social processes.

Traditionally speaking, the heritage attributes that stand out —generally linked to the monument— and what are being discussed today are the social relations that help explain the loss of heritage, which has continuously accumulated throughout history.[29]Heritage: group of morals gathered through tradition or coherence. In other words, to consider heritage less from the perspective of attributes and more from the social relations that constitute them. This focuses on the opposite angle to that of accumulated memory; that is, from logic and forms of production of oversight, to understand the processes of generation of heritage from its origins (economic, cultural, political), and less from the object of destruction (monument); to build new ways of producing sustainability in the historical accumulation of heritage (historical value).

This methodological change will allow one to heal by example, but in reverse: to see from where one can witness what is lost, through a balance between what is recovered and what is destroyed, in levels of supposed “superior values” originating from politics, from war, or from the economy, that end up subsuming the very own institutions destined to mitigate such oversight.

The concept of urbicide is central to the understanding of this process, because it helps one understand what is being lost, and from this, what must be kept as well as what must be built.

Patrimony: Polysemy and Fetishism

According to the dictionary, the word heritage comes from Latin and is composed of both patri, which means father, and onuim, which means received; that is to say, it is received through the fathers’ lineage. This gives it an extremely dynamic definition that involves an historical process with explicit characters: those that receive (is received by) and those that transmit (through the paternal line); that is to say, actors that interact as patrimonial subjects in relation to the dispute over inheritance (Carrión, 2010).

This notion of patrimony does not define goods or things —be them material, immaterial, or spiritual— but is instead a relationship that delimits an area of particular social conflict: legacy or inheritance, and it does so according to the correlation of strength from heritage subjects in specific places and moments in time; which is, ultimately, what defines the conditions of power of each, because without appropriation —as the basis of power— there is no patrimony.

It is in the context of mechanisms of transmission of patrimony —proper of the process of conflict— that achieves the historical sustainability of the process, a situation that is very similar to what happens within the nucleus of a family and between the father and his sons. In other words, patrimony generates power that is born from property and from the weight that patrimonial subjects have in their interactions: someone must take over so that heritage may exist and, without a doubt, property is a historically constituted social relation.

In this way, patrimony is the result of a historical process of continuous accumulation of time and, at the same time, a mechanism that produces history; all this thanks to the constant transformation of patrimonial mass (heritage) through the transmission of patrimony among its subjects, under a double situation: democratization of patrimony (property and power) and the increase of the value of history (adds time to the past); that has nothing to do with politics of conservation. The history of this social relation —which defines productive inheritance— denies heritage fetishism as well as containment practices of history in its unique moment: origin.

In this last instance, heritage envelops, on the one side, a property that gives the heritage subject power. And on the other side, a transference or inheritance that —regardless of how familiar or private it is— must be distributed by the public sector, be it through: the courts of justice (public institutional framework) or the civil code of conduct (social contract) that determines the protocol to follow. Heritage within society is not very different: conflict must be processed with legal, institutional, and public policy laws, because otherwise, it is the market that will create its own logic. More so —as is occurring now— there are deregulation processes that aim to attract capital, transforming heritage into physical capital.

Heritage can only be conceived historically since there is a logic of power that is sustained in the relations between heritage subjects that (re)produce, transfer, and consume. If this is indeed so, then three great heritage moments throughout history can be found: the first, linked to modernity, where the state appropriates patrimony (institutional heritage), to conceive it as an “ideological apparatus” that constructs and legitimizes official history, thanks to the pleasures generated by its spectacularization and the massification of its contemplative consumption,[30]Subsequently, it will acquire a singular weight, that of an exchange value, exactly when the capitalist model is consolidated and when tourism and the real estate sector give new meaning to the … Continue reading coming from the hyper urbanization of the population.

In this instance —characteristic of the current heritage situation— the foundational fact of the birth of historical heritage —because heritage has not always existed— starts on two consecutive paths: on one hand, monuments constructed as relevant social construction, such as churches (value of use) but that require durability over time, as a testimony of a period due to the importance of its historical use or function or because of the wealth found in its material production. In this case, what exists is the increase in its functional quality (value of use) and the need for a sense of memory (historical value). On the other hand, there is the need to make public the historical facts of yesterday,[31]Both produce “official history”. through the explicit construction of a new patrimonial good (monument) that from the beginning is born with a historical value, as if it were its value of use. Currently, there is a difference between patrimony as a value of use, and historical patrimony as a historical value.

The following situation is related to the period of the first and second world war, when there were significant destruction of European historical patrimony, localized in the most emblematic countries of the continent. From this moment forward, Europe became the main space for the eradication of thought -above all- of politics of patrimony that were critically universalized.[32]The Second World War from one day to the next destroyed all the cities heritage sites, while in Latin America the erosion of these sites was caused by the socio-economic conditions and the … Continue reading To formalize these proposals, Letters were used —that adopted the name of the city where they were written—[33]Letters from Athens (1931) were written by European specialists. In Venice (1964) three “strangers” from Peru, Mexico, and Tunisia participated. Then, in 1972 the first convention on the … Continue reading and the Conventions, both under the principal of the conservation of monuments on its various degrees, that were incapable of understanding the wealth of particular phenomena, nor of stopping the destructive processes.

The historical condition of heritage surpasses that paradigm,[34]According to Tomas Kuhn “(…), the paradigm makes reference to the “conjunction of practices that define a scientific discipline during specific periods of time”. which dominated heritage that was sustained in the devotion of certain goods —as essential objects, be them tangible or intangible, material or immaterial— that turned into heritage fetishism,[35]It is very close to the proposal of Marx (2000) in regards to its sense and content on “mechandise fetishism”. insofar that it leaves social relations out, that: (re)produce or hide behind good attributes. This historical vision[36]Here is where the definition of “colonial monument patrimony” is recorded, as the determination of existence of a foundational center of value for Latin America, and that also ends up defining … Continue reading settles on the social production of heritage, occurring at specific moments in time, and in specific places and societies.

Historical centers for example, were conceived as physical goods that had certain attributes (conjunction of monuments) rather than relations. This is why when such centers are historically analyzed, as social production, the centers quality —which is a fairly relative definition— becomes fluid; and the historicalcondition is reduced to finding the moment of its genesis to apply politics of conservation. This way it is emptied of history and filled with fetishism: this is why conservation produces negation of the historical condition of the center; so much so that when giving value, heritage goods produced during the Spanish Conquest highlight colonial domination through the attributes given to the monument —or to the conjunction of monuments— and freezes history in the moment of its origin, which denies the continuous process of accumulation of time, which in turn permits multiple and simultaneous lectures from different times under the framework of a palimpsest (historical value).

This way the historical condition is liquefied when the monument becomes the determining element of the existence of heritage, rather than the other way around: heritage is an inheritance or creative transmission that gives a certain good an increase in historical value. This is why they do not accept that for example, the demarcation of an historical center is born from urban politics and from the correlation of strengths of patrimonial subjects and if they believe that the delimitation comes from a creative demiurge that falls from heaven, incarnated by a deity or an expert.

In reaction to this heritage fetishism, there have appeared two visions. The first, understood as physical capital, where it must reproduce and accumulate to obtain significant economic profit (value of exchange). In this regards, tourism is gravitation, although the commercial and the real estate sector (Rojas, 2004) are as well. And the second takes its first steps away from the concept of heritage as social capital, while allowing institutions to strengthen and improve social cohesion.

Historical heritage can also be considered a polysemic definition,[37]As well as the concepts of democracy, development, and decentralization, among others. since it has multiple and plural ways of being conceived, so much so that it breaks away from hegemonic definitions inscribed in the logic of unique thought, which does not accept dissent. Below we can see various ways that show said reality:

- The historical itinerary —proper of the passing of time— gives way to a sequence that, according to Choay (2009), moves from the connotation of family (family heritage) to economy (economic heritage), to the field of law[38]This recognition of the legal parameters has two important implications: first, it is located in the right, and second, it converts it into a public process that is regulated –through a social … Continue reading and then continuing into the political field (heritagism),[39]It refers to patrimonial subjects (patriarchal) that consider public goods as their own; that is to say, they appropriate the public. all with the singular weight of a sense of property. Heritage is what is owned within different forms, which the right ended through its formalization.

- The fragmentation of heritage types is expressed in three different ways: one, linked to its dichotomic character, material or immaterial, as well as tangible or intangible; second, related to the sectorial field of patrimony: industrial, cultural, military, architectural, or musical; third, refers to what Bourdieu (1999) denominated as the “effect of the place”, which suggests a heritage universe according to the space where it is constructed. Since historically the concept arose in Europe —in modern times— this is the starting point from where it spread to the rest of the world; something that now is not possible due to the emergence of new realities on a global level;[40]“My work in the American Continent for that of over 20 years, in contrast to the work conducted in my country and the rest of Europe, has made me realize that to solve a problem of conservation of … Continue reading this is the case of glocalization —defined by Robertson (1992)— of heritage, which pluralizes it. The richness of heritage resides in its accumulation (notion of antiquity) and its diversity.

- The theoretical-methodological positions define the characteristics of the object of thought: the traditional vision puts emphasis on denominated heritage goods, be they material or immaterial, which are the most widespread. This vision is in question due to the three positions that are currently being developed: one that it arises from the definition of physical capital, which must reproduce and maintain high earnings (Rojas, 2004) and the other from what is meant by social capital, which strengthens institutions and social cohesion. Additionally, there is also what is conceived as the stage of conflict between heritage subjects and the sustainable transmission of inheritance.

As polysemy grows, so too does the surpassing of heritage fetishism, one or the other registered under a historical condition. But also, it is a fact that the process of urbanization of society has determined that the entire concept of a city, as the space with the greatest density of heritage, and everything within can be considered heritage, since the entire city and all its parts have a use value. However, only some parts reach the status of historical heritage, due to the continuous accumulation of historical value. This is why urbicide can act over heritage, over historical heritage, or over both; depending on the intended strategy.

Urbicide: The Social Production of Oversight

The term urbicide was coined for the first time during the sixties by science fiction author Michael Moorcock (1963). A few more years passed before the term was used in urban studies and subsequently appeared in two different methodologies: the first, related to the devastating effects of war on cities, and the second inextricably linked to the impacts created by repairing and re-enabling run down cities, especially in those places considered lower income neighborhoods. New York is an example of the previous (the Bronx) and Chicago as well. After these two attempts —one being the city acting as the stage and the second as a constitutive part of the city— the concept practically disappeared, supposedly due to the lack of understanding of urban reality.

However, this notion should be developed given how appropriate it is for explaining some of the phenomena inherent to neoliberal urbanism so current in Latin American cities. It is even more appropriate when linked to the concept of heritage, in this historical context it becomes something akin to a physical asset and thanks to the relationship between these two concepts —urbicide and heritage— it becomes that much more feasible to find just how much potential it has.

Urbicide is a neologism, a compound Word made up of: urb a synonym for city, and cide the word for death: together, the death of a city.[41]A term originating from the Latin words: urbs, city; caedere, cut or murder and occido, massacre. But, just as homicide means the death of a person, femicide the death of a woman for reasons related to gender, or suicide the self-inflicted death of a person, urbicide does not mean the death of every city, nor the end of the complex reality of a city; rather it indicates the murder of a particular city or certain essential elements within it, a murder brought about by clearly defined processes.

You could say that the concept is still very much in development, its definition summed up as the liturgical assassination of a city product of aggression and premeditated action carried out with order and explicit intent; in other words, murder or violence against the city for urban motives. In principle, these are considered military, financial, cultural or political acts that: i) eliminate identity, symbols and the local community’s collective memory situated in the city itself; it even extends to a change in definition, citizens become clients or consumers (civitas); ii) privatization, a phenomena that concentrates and subjugates politics and public institutions to the interests of the market or a central power, removing self-government and fair representation (polis), and iii) the destruction of public spaces considered important for the community such as plazas, parks, monuments and other infrastructure (bridges, highways) such as libraries (urbs).

To illustrate these statements, and to provide an example, the following cases are considered emblematic of urbicide:

1. The most evident effects are probably related to war and fratricidal conflict happening all over the world since time immemorial, although today we can safely say that the main stage or setting for these conflicts are todays cities, thanks to prevalent planetary urbanization. We really don’t have to go too far back in time to find several cases of this kind of devastation in cities:

- The emblematic city of Guernica —destroyed in 1937— is important given it was an opportunity for rehearsal for the mass bombings that came later in the Second World War. But it also has additional importance because of the devastating Italian and German air raids that occurred during the Spanish civil war. The strategic points that were targeted for bombing were: the bridge, the train station and the city’s Eastern highway, supposedly to trap the Basque forces. However the true objective was to completely and utterly destroy the city of Guernica due to its cultural and historical significance for the Basque country, and because it was a sanctuary for freedom and democracy; in complete defiance of monarchic power, centralization and fascism embodied by Franco. This explains the in excess of 7% mortality rate, and the destruction of approximately 74% of the buildings in the city, and subsequently the severe blow to Basque morale.

- The impact, product of the Second World War, on many European cities such as Warsaw, Berlin, Tokyo, and perhaps the worst of all, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The first in that small list were witness and victims of military violence as the central conflict points or as cities targeted for annihilation, the last two cities were razed to the ground toward the very end of the war, all in a bid to display supremacy over the rest of the world.

- From the nineties onward (in the last century) new wars were developed on two new fronts: The war in the Balkans, according to the former mayor of Belgrade Mr. Bogdan Bogdanovic, was almost exclusively waged against cities and designed to undermine the cultural values heavily concentrated in them. These cities included Sarajevo, Belgrade, Mostar and Grozny, but there were also cities that played host to the split in the Soviet Union, giving birth to the Russian Federation, the most notorious being nations such as Chechnya and Georgia among others.

- Then came the “preventive” wars instigated by George W. Bush, President of the United States of America, or the “necessary wars” continued by the Nobel Peace Prize winner Barack Obama, which used the perfidious attack of the Taliban on the 11th of September 2002 on the most iconic and symbolic buildings in the U.S. as a pretext to start said wars: New York’s Twin Towers, true expressions of economic power, the Pentagon in Washington, home to the Department of Defense, and the Whitehouse which ultimately failed in its attempt, said building being the center of political power in the country. The immediate reaction was to invade Iraq and Afghanistan where the main cities of Bagdad (the capital of Iraq) and Kabul (capital of Afghanistan) among others suffered much extending to the destruction of cultural heritage through war sanctions, looting and military attacks.

- Of course, the outbreaks of conflict in the Muslim nations; the most significant being Libya (Tripoli and Benghazi) and Syria (Damascus, Aleppo) certainly can’t be left out, as well as the countries participating in the “Arab Spring” such as: Tunisia with its homonymous capital and Egypt affecting both Cairo and Alexandria.

- Long-standing wars must also be included; the Arab-Israeli conflict where Jerusalem, Haifa and Gaza to name but a few have suffered the cultural setbacks associated with a permanent state of war. The internal conflict present in Colombia must also be included to which we must also add illegal economic practices (illegal arms trade, drug running, the trade of chemical precursors and human trafficking); all contributing to the destruction of several cities in acts of terrorism. Far less can we forget the effects of the Lebanese civil war, Israeli attacks and the internal conflict between Christians and Muslims that ruined the millenary cultural heritage present in Beirut and beloved by its residents.

These cases generally form part of military strategy and tactics created to submit the adversaries’ cities both physically and morally by murdering people (either selectively or in their masses), isolating them (destroying air and sea ports), limiting services (power and drinking water), blocking supply routes (effectively blocking food and spare parts) and, if the previous wasn’t enough, the destruction of cultural icons in each city, churches, mosques and libraries, said infrastructure constituting urban landmarks, signs of a shared environment, a life lived in community.

2. Another element thought to cause urbicide that must out of necessity be mentioned in this paper is urban violence, especially considering its importance during the last 20 years in Latin America, in particular the rising number of homicides and murders in cities.[42]If measured by the murder rate in 1980 there were 12 murders for every one hundred thousand inhabitants, which in 2006 rose to 25,3 (Kilsberg, 2008). If, historically speaking, a city was thought to be a cause of violence —through etiological studies— today we can affirm that there are far more negative impacts on a city caused by violence; so much so that objectively speaking (actual violent events) and subjective violence (fear) have become urban elements that reject the formation of a city under the category of urbicide.

- Urban violence unfolds over time under a clearly defined temporal logic: the cultural calendar that makes each week different, and weekends different from weekdays; establishes the difference between daylight and night hours. There’s clearly a criminal chronology that affects urban dynamics and the city itself, so much so that in general terms the city can even fall into disuse: there are no longer cities that exist 365 days or 54 weeks of the year and all 24 hours of the day.

- Violence within city limits tends to develop in open spaces, guided by an explicit urban logic that clearly affirms the existence of a criminal geography which —little by little— takes over the city, either by engendering a perspective of insecurity or through diverse criminal acts. The perception of insecurity is diffuse and ubiquitous though linked to certain territorial stigmas; whilst the reality surrounding these criminal acts originates in existing urban fragmentation: Banks are robbed where there are Banks to be robbed, crime in the city center is different to the crime in outlying areas of the city, violence in public spaces differs to those crimes committed in private.

- Additionally, violence in the cities also has a devastating effect on social interaction and on everyday life, to an extent where people are no longer as supporting or caring of each other, people take it upon themselves to exact justice for their wrongs leading to vigilantism; people buy arms, learn self-defense, it can lead to public lynching and open the door to the burgeoning business of private security. Citizens living under these conditions consider strangers possible aggressors, and public spaces are considered areas out of control (Carrión, 2010)

- Without doubt urban violence decreases a city’s fundamental bases: time, space, citizenry and, due to a lack of positive response, discredits institutions and public policy. In summary, urbicide exists largely due to violence, violence being its main benefactor —and on a parallel— also leads to collective memory loss.

3. One of the most significant impacts comes from the economy and the emplacement of urban neoliberal logic.

- The modification and ousting of the structure and general conditions inherent to the accumulation of communal memory caused, to name an example, the irreversible crisis in the city of Detroit.[43]Among other indicators the population has fallen to half what it was 50 years ago, unemployment is triple what is was in the year 2000; 47% of property owners don’t pay municipal tax which has led … Continue reading The global change to the model of urban creation initially born and developed around the automobile industry —back when production in this powerful industrial sector was sheltered in a assigned space— caused a deep depression due to the breaking down and re-location of productive processes at a planetary level, in which the city was left outside the newly formed economic circles, as is illustrated in the following graph created by Celata F. (2007):

General Motors Productive Structure

- Looking at it from a different perspective, a more economic and intra-urban viewpoint, certain urbicidal phenomena are caused by the following elements: i) the growing clout of property markets within an urban economy; ii) the presence of large-scale urban projects (LCUP) stemming from the urban planning crisis and the demand of the real estate sector; and iii) the transformation from a segregated to fragmented city —condition inherent to an insular city (Duhau)— which creates a constellation of discontinuous spaces with “exception areas” or “free zones” where commercial development —in other words private businesses— set up shop to “colonize” the area and remove what are generally lower income families and communities, obeying the laws of gentrification.

These exception areas are generally speaking nurtured by a manner of tailor-made urbanism product of concessions made to the real-estate sector, made possible by the euphemisms of partial plans or deregulation of the land and real estate market, or encouraged by tax incentives. This ultimately expresses itself in the form of changes to land-use regulations, urban density regulations, the urban skyline, tax exemptions and the creation of subsidized credit, forming gated communities that break the social conventions of public spaces, homogenous provision of services and the ousting of lower income communities; all serve to increase urban segregation, eroding social capital and weakening efficient city governance.

4. It is hardly affordable to ignore the logic of innovation so pervasive the world over, product of the techno-scientific revolution in communications, a revolution which is by its very nature the opposite of preservation and memory; said innovation is accompanied by the underlying thesis that success depends on rapid change, hence why everything becomes obsolete in the short term, continually replacing the old with the new.

5. Lastly, another element that should be considered “urbicidal” is the increasing effects of climate change and its urban consequences. The planet’s vulnerability has increased and done so in different scales in social and territorial aspects. The earthquakes and the accompanying tsunamis in Haiti and Chile; cyclones in Central America and the Philippines; floods in China and New Orleans and drought in Australia are leaving devastating effects on our cities and the resident population.

In conclusion, urbicide refers to, on the one hand, practices that steer towards “oblivion” or memory loss; an issue currently defined in what is called the “Clash of Civilizations”. It’s all about procedures and not hard fact, procedures pertaining to much broader contexts. The objective is to destroy the collective and historical memory of the community which is, generally speaking, the social glue, what provides the communities with a collective identity (civitas), and in destroying it makes it possible to subjugate these communities to a supposedly more developed and advanced society.

But on the other hand, urbicide is mainly linked to urban economy; an economy which leads to the erosion of public institutions and self-governance (polis) and does so through privatization or corruption, working to deteriorate the material base of the city (urbs); to favor urban development inherent to the logic or philosophy of a neo-liberal city.

(IN)Conclusions

This paper does not intend to give any conclusions, since it is an open topic that is still being built and formulated. However, it is important to point out that heritage, as urbicide, is a social construction and therefore also an historical construction. The first idea leading to this stance is that of heritage as a polysemic definition and as a concept that surpasses heritage fetishism, which marked it from the beginning and which led to the emptying of society.

The logic of the monument without history, or heritage without society, is a reality that cannot continue to be accepted and that must be surpassed. It cannot be possible that memory —which is a confrontational space— be void of history (maybe the end of history that some were expecting?), when what we should be doing is the complete opposite: combining all time periods as well as the future, so that they become objects of desire that can be equally distributed among society. For this it is essential to build a collective heritage project, together with the most important heritage subjects, and develop integral and multidisciplinary visions that go beyond conclaves and traditional technocracies.

The city is the place with the greatest concentration of population in the world, it is the space with the highest presence of heritage on earth, also expressing the greatest diversity measured by use value (heritage), historical value (historical heritage), and exchange value (economic heritage); this is why social production of urbicide has led to the loss of memory and the production of oversight on behalf of all humanity. Heritage is an issue of the city and is an issue of extreme importance. Urban centers (which are all historical) are the urban space with the highest presence of historical heritage; making the need for urban politics indispensible. However, urbicide presents itself in various ways (war, economy), making the need to build cities for peace almost unavoidable, as well as the need for stable and well distributed urban economies, cultural politics that respect diversity, politics that incorporate the latest technologies, and environmental politics that address global climate change, among other things.

Urbicide appears to show the need to reestablish the cities right to produce urban citizenship, because democratization of patrimony is a way to democratize the city. More so if we consider that urbanization is being produced without the city, that there are urban processes that deny the city, where public spaces end up being hideouts rather than places for interaction.

This is why we must continue to consider the dilemma in regards to heritage: does it belong to humanity or the market? We must also continue to affirm that the antidote to urbicide is the right of the city, because the city and all its parts are essential our heritage.

Bibliography

Bourdieu, Pierre (1999): La miseria del mundo, Akal, Madrid.

Carrión, Fernando (2010): El laberinto de las centralidades históricas en América Latina, Ediciones Ministerio de Cultura, Quito.

Choay, Francoise (2007): Alegoría del patrimonio, Gustavo Gili, Barcelona.

Del Pino, Agnes (2013): “Impactos del turismo en sectores patrimoniales”, paper presented at the International Seminar: “La intervención urbana en centros tradicionales con enfoque social”, Instituto Distrital de Patrimonio Cultura de Colombia, 27 and 28 November.

Marx, Carlos (2000): El capital, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Mexico City.

Klisberg, Bernardo (2008): “¿Cómo enfrentar la seguridad ciudadana en América Latina?, Revista Nueva Sociedad n° 215, May-June.

Robertson, Roland (1992): Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture, Sage. London.

Tomas Kuhn (1971): La estructura de las revoluciones científicas, Fondo Cultura Económica, Mexico City.

Rojas, Eduardo (2004): Volver al centro: la recuperación de la áreas centrales, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington.

Fernando Carrión M.[44]President of Organización Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Centros Históricos” (OLACCHI) and academic from the “Facultad Latinoamérica de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) in Quito, Ecuador.

Translated by Christopher Clarke.

| ↑1 | En 1990 la población del Centro Histórico fue 81.384 habitantes, 20 años después se redujo a 40.913 (Del Pino, 2013). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Los paradigmas hegemónicos han sido funcionales a estos procesos, por ejemplo, gracias a las políticas de turismo, de gentrificación y de conservación, entre otras. |

| ↑3 | Situación muy parecida se vivió con la Segunda Guerra Mundial en Europa, que dio lugar justamente a un impulso muy fuerte de las tesis de la restauración y la reconstrucción monumental. |

| ↑4 | Tres grandes coyunturas patrimoniales ha vivido la humanidad: la primera con la primera modernidad, la segunda con la guerra mundial y ahora con la globalización. |

| ↑5 | Al momento son 187 ciudades consideradas patrimonio de la humanidad, las que deciden conformar la Organización de Ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad (OCPM), para intercambiar experiencias, difundir conocimientos, generar asistencia técnica, entre otras (http://www.ovpm.org/main.asp). Además se debe señalar que actualmente (año 2013) están catalogados 981 sitios: 759 culturales, 193 naturales y 29 mixtos, en 160 países del mundo entero. |

| ↑6 | Por monumento se entiende según el DRAE: “Obra pública y patente, como una estatua, una inscripción o un sepulcro, puesta en memoria de una acción heroica u otra cosa singular. Construcción que posee valor artístico, arqueológico, histórico, etc.” (resaltado nuestro). |

| ↑7 | Acervo: conjunto de bienes morales o culturales acumulados por tradición o coherencia. |

| ↑8 | Posteriormente adquirirá un peso singular el valor de cambio, justamente cuando el modelo capitalista se consolida y cuando el turismo y el sector inmobiliario le dan una nueva connotación al patrimonio: capital físico que puede generar altas utilidades a quien lo posea o explote económicamente. |

| ↑9 | Tanto el uno como el otro producen “historia oficial”. |

| ↑10 | La Segunda Guerra Mundial destruyó de un día para otro el patrimonio de las ciudades, mientras en América Latina la erosión vino de las condiciones socioeconómicas y de las características de la urbanización. |

| ↑11 | La Carta de Atenas (1931) fue redactada solo por especialistas europeos, en la de Venecia (1964) par-ticiparon tres “extraños” provenientes de Perú, México y Túnez y luego en 1972 se realizó la primera Convención sobre la protección del patrimonio mundial, cultural y natural con la participación de cerca de 80 países del mundo. |

| ↑12 | Según Tomas Kuhn “(…), el paradigma hace referencia al “conjunto de prácticas que definen una disci-plina científica durante un período específico”. |

| ↑13 | En mucho se acerca a la propuesta de Marx (2000) respecto del sentido y contenido del “fetichismo de la mercancía”. |

| ↑14 | Aquí se inscribe esa definición del “patrimonio monumental colonial” como determinación de exis-tencia de un centro fundacional de valor en América Latina que, incluso, termina por definirlo como un centro homogéneo y colonial (casco colonial, estilo colonial) que se proyecta. Lo colonial no fue ho-mogéneo, sino de la imposición de la cultura y la economía de los conquistadores a los conquistados. Si bien fue una fase histórica que no se puede olvidar, ello no puede conducir a sublimar. |

| ↑15 | Como también lo son los conceptos de democracia, desarrollo y descentralización, entre otros. |

| ↑16 | Este reconocimiento de lo jurídico tiene dos implicaciones muy importantes: primero, se ubica en el campo del derecho y, segundo, lo convierte en un proceso público que está normado —a través de un pacto social: eso es una ley—, que son formas de procesar el conflicto de la heredad. |